Plato's High-Minded Authoritarianism

Or, "The Importance of Choosing Wise Rulers (Wisely)"

In the modern world, authoritarianism is self-serving. Donald Trump is obviously the peak example of this phenomenon, but he is far from the only one. Vladimir Putin is reportedly worth up to $200 billion USD. Viktor Orban in Hungary has used EU farm subsidy programs to enrich himself and his allies. Authoritarian leaders around the world routinely jail their political opponents for fear of losing their grip on power.

In this context, it is easy to dismiss Plato's peculiar political philosophy. A well-known critic of democracy, Plato envisions in The Republic a utopia, his "city in speech," the rulers of which are philosopher-kings who are the sole decision makers for the society as a whole. He proposed a system that presaged eugenics, in which talented children were to be taken from their families and educated by the ruling classes, while untalented children were to live and work with the lower castes. What could we learn from Plato about political philosophy, when his views are so easily applicable to horrific modern anti-democratic regimes?

Plato's ideal society, however, functions much differently from any current or past government (with the possible exception of Sparta, whose governance structure Plato seems quite taken with). It's unclear that his political ideas, even if they are worth considering ex ante, would work in practice to create a functioning state. Nevertheless, it's worth looking into his politics, as they can shine a light on a more benevolent authoritarian style - which, if authoritarianism is to be the order of the day (and that is certainly where things are trending), is preferable to the self-serving quality that currently reigns.

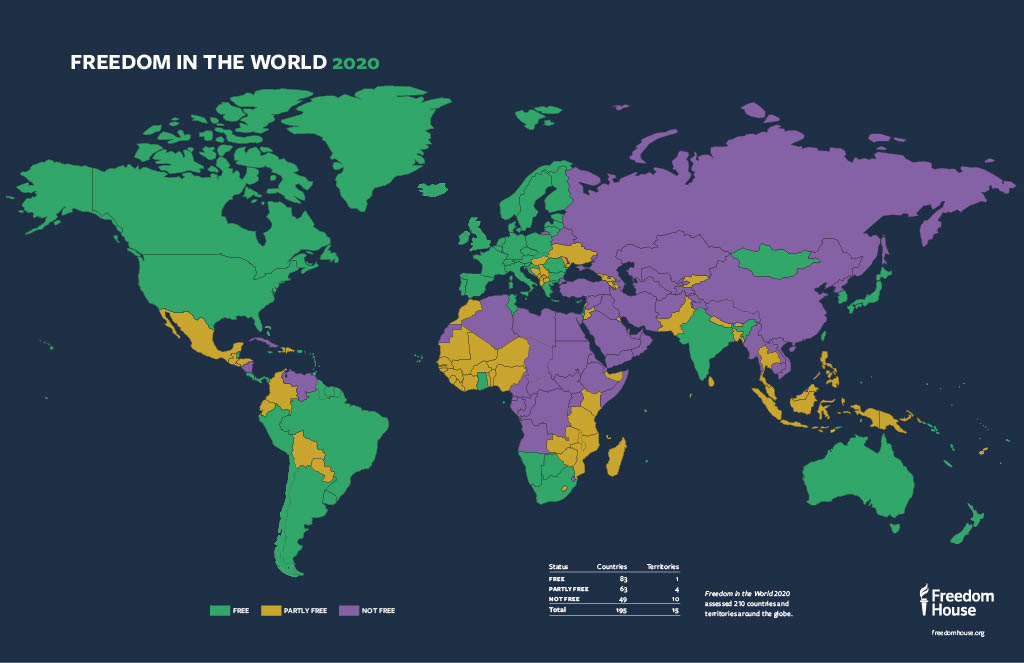

Freedom House map displaying countries as free, partly free, and not free.

Plato's antidemocratic argument

What inclined Plato away from democracy? Some answers deal with his personal life. Plato was born into Athenian aristocracy, and he was in his twenties when he saw Athenian democracy collapse at the end of the Peloponnesian War. A few years later, a jury democratically convicted his teacher and greatest influence, Socrates, of frivolous crimes and sentenced him to death. The philosophical reasons for Plato's antidemocratic beliefs are perhaps more interesting yet. Bertrand Russell lists them as follows:

Plato believed Goodness and ultimate Reality to be timeless. The best state, he reasoned, is that which most closely aligns itself with the timeless nature of Goodness. Such a state will change infrequently, and will be led by those who "best understand the eternal Good."

Russell identifies Plato as a mystic at core; similar to Pythagoras, Plato "endeavoured to set up a rule of the initiate..." Those who do not know the Good would, if permitted to rule, corrupt the state. Plato's certainty about this is tied to the high value he places on "enlightenment."

Rulers need to be well-educated, in Plato's mind. This seriously limits your options, even in modern developed countries. (In a democracy, those who choose the rulers are also, in part, the rulers!)

Most condescendingly, Plato "took the view that leisure is essential to wisdom." Most philosophy, it is true, has not been written by those who have day jobs. Plato's position here implies that those who are not independently wealthy, those who have to work for their food, cannot be wise enough to rule; this encourages oligarchy at best.

These views on the role of wisdom in politics inform Plato's "city in speech," as written in The Republic. Features of this utopian society include communal ownership and child-rearing among the ruling classes, severe censorship and propagandistic education, and a sharp delineation of caste. The ruling classes will initially be chosen for their wisdom, and thereafter will generally be composed of the progeny of the rulers (who will be genetically superior).

Arguably, Plato's antidemocratic arguments above are somewhat anodyne. Shouldn't we want our rulers to be exceptionally well-educated? Shouldn't we want them to have a well-developed sense of the "Good," even in a democracy? It's hard to see, at first, how these arguments lead to authoritarianism, much less the extreme form of authoritarianism presented in The Republic.

Whence wisdom?

Plato's antidemocratic arguments rest on a pair of assumptions:

There is such a thing as "wisdom," and;

A constitution can be devised that will give wisdom political power.

If we take these assumptions to be true, then perhaps Plato's benevolent authoritarianism is more attractive. Wise leaders will decide what is best for the populace, certainly much more ably than the uneducated masses will do for themselves. The government will be stable and conservative, but ultimately responsive to questions of justice.

Of course, it's not at all clear that there is such a thing as "wisdom." If "wisdom" is doing that which is right, the question becomes: for whom? Different countries, and different classes within a country, will have divergent interests. Is doing what is right simply attempting to broker compromise among different interests? Then surely members of the ruling class cannot be neutral, as they have interests of their own. This problem is concentrated when power lies in the hands of a single authoritarian ruler.

So "wisdom" resists definition. Now, let's assume that we come up with a definition of "wisdom" that all can agree to. It still seems unlikely that we can satisfy Plato's second assumption, namely that a constitution can be devised that gives wisdom political power. Russell seems skeptical:

It is clear that majorities, like general councils, may err, and in fact have erred. Aristocracies are not always wise; kings are often foolish; Popes, in spite of infallibility, have committed grievous errors. Would anybody advocate entrusting the government to university graduates, or even to doctors of divinity? Or to men who, having been born poor, have made great fortunes? It is clear that no legally definable selection of citizens is likely to be wiser, in practice, than the whole body. (p. 107, emphasis mine)

This, Russell says, is the ultimate reason for democracy. It is impossible to isolate a legally definable subset of individuals as being more "wise" than the polity as a whole.

Even if our autocrats were "wiser," more benevolent, less self-serving than Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, the states they lead would be weaker and more prone to instability than democracies with strong institutions. Unfortunately, autocratic leaders are rarely selected for their wisdom or humility. Rather, they are selected for their charisma - a trait often tied more to narcissism than wisdom.

Wisdom in politics

The worthwhile takeaway from Plato's political philosophy is that it is paramount that we choose wise leaders. Lacking a good definition of "wisdom," we can refine this to say that we should choose leaders who have the skills, talents, and experience to meet the moment. We should choose leaders who complement each other and have a track record of working toward the common good. The leaders we choose should be humble, not charismatic.

We can make the choice of leader democratically! Often, however, democracies produce antidemocratic leaders - increasingly so in the modern world. Choosing "wise" leaders, together, is an increasingly weighty responsibility.